Aligning Your Financial Due Diligence Purpose and Process

Does your foundation’s financial due diligence process align with your purpose and values? What did we learn from a landscape analysis of funder processes?

For most funders, a review of grantee financial information is an integral part of the due diligence and grantmaking process. Recently a private foundation commissioned BDO’s Nonprofit and Grantmaker Advisory team to conduct a landscape analysis of grantee financial due diligence practices among 15 of its peer funders (large US-based private foundations). The client sought this information to inform their own financial due diligence process, which BDO has since helped them to redesign.

The landscape analysis focused on understanding the purposes for which these foundations conduct financial due diligence (FDD) and how this process looks in practice. Each participating foundation was asked to complete a survey on how they conduct FDD, share any relevant process documents, and participate in a follow-up interview with BDO.

Unsurprisingly, given that there is no universal legal or professional standard for financial due diligence in grantmaking, the process was different at each foundation. That said, there was one stated central component of the process common to each funder in the study, which is that a goal is to “get to yes.” In other words, the FDD process was (in almost all cases) not intended to disqualify grantees from potential funding opportunities, but rather to inform other aspects of the grant, such as size, duration, monitoring, etc. (For this analysis, we focused only on financial due diligence, understanding and acknowledging that other types of due diligence may impact grantmaking differently.)

To achieve some sense-making given the varying approaches to financial due diligence, we constructed a framework to better understand and create comparisons among the foundations’ practices. The framework considers two key dimensions of FDD: purpose and content.

Purpose

Broadly, most grantmakers would agree that the purpose of financial due diligence is to safeguard a funder’s investment by ensuring that a grantee is capable of fulfilling the goal of a grant. How that purpose is carried out in practice, though, can vary widely among grantmakers. We developed a spectrum of ways that grantmakers use financial due diligence to serve that purpose, identifying three typical approaches: “supportive” (providing support and resources to grantees who may need additional capacity), “protective” (approaching with caution grantees who may show financial or other challenges), and “neutral” (ensuring that a grantee is legally eligible to receive charitable funds—a minimalist FDD approach).

The grantmakers falling into the supportive category focused their efforts on offering flexible funding and/or proactive grantee capacity building measures. For these foundations, an understanding of an organization’s financial health may prompt a shift in funding strategy from a project grant to general operating support, or to make larger, upfront grant disbursements to support a grantee experiencing temporary cash flow challenges. Some foundations provide additional capacity building support through trainings, other types of technical assistance, or facilitated connections to other funders if donor concentration is a concern.

In contrast, actions taken by funders who adopted a more protective approach were oriented toward caution in the disbursement, monitoring, and/or management of grant funds. Some funders introduced additional monitoring and reporting requirements on grantees that showed potential financial issues. Others reduced the size of a grant or increased the number of grant disbursements and decreased the dollar amount per disbursement to protect financial resources.

Between the supportive and protective sides is a more neutral purpose. These foundations focus their FDD mainly on the core requirement of verifying that funds are being used for charitable purposes. They do this by confirming the charitable status of potential grantees or exercising expenditure responsibility. Some also consider any tipping concerns.

Content Reviewed

The other dimension of the framework considers the volume and range of the content collected, reviewed, and analyzed during the financial due diligence process. Is it a modest review where data collection and/or analysis is focused on basic eligibility? Or a substantive review including significant document gathering and analysis of multiple financial metrics and parameters?

The most modest review of grantee data consisted of ensuring an organization’s eligibility to receive charitable funds, which could be as simple as verifying its 501(c)(3) status.1 Further up the scale toward a substantive review are foundations that collect additional documentation (budgets, audited financial statements, etc.), and calculate key metrics for a more in-depth analysis of grantee financial health. At the top of the substantive scale are those foundations that include a more qualitative review of grantee financial management practices, looking at the systems and staff in place in the organization’s finance office, and in some cases reviewing grantee financial and other risk management policies and procedures.

Mapping on the Framework

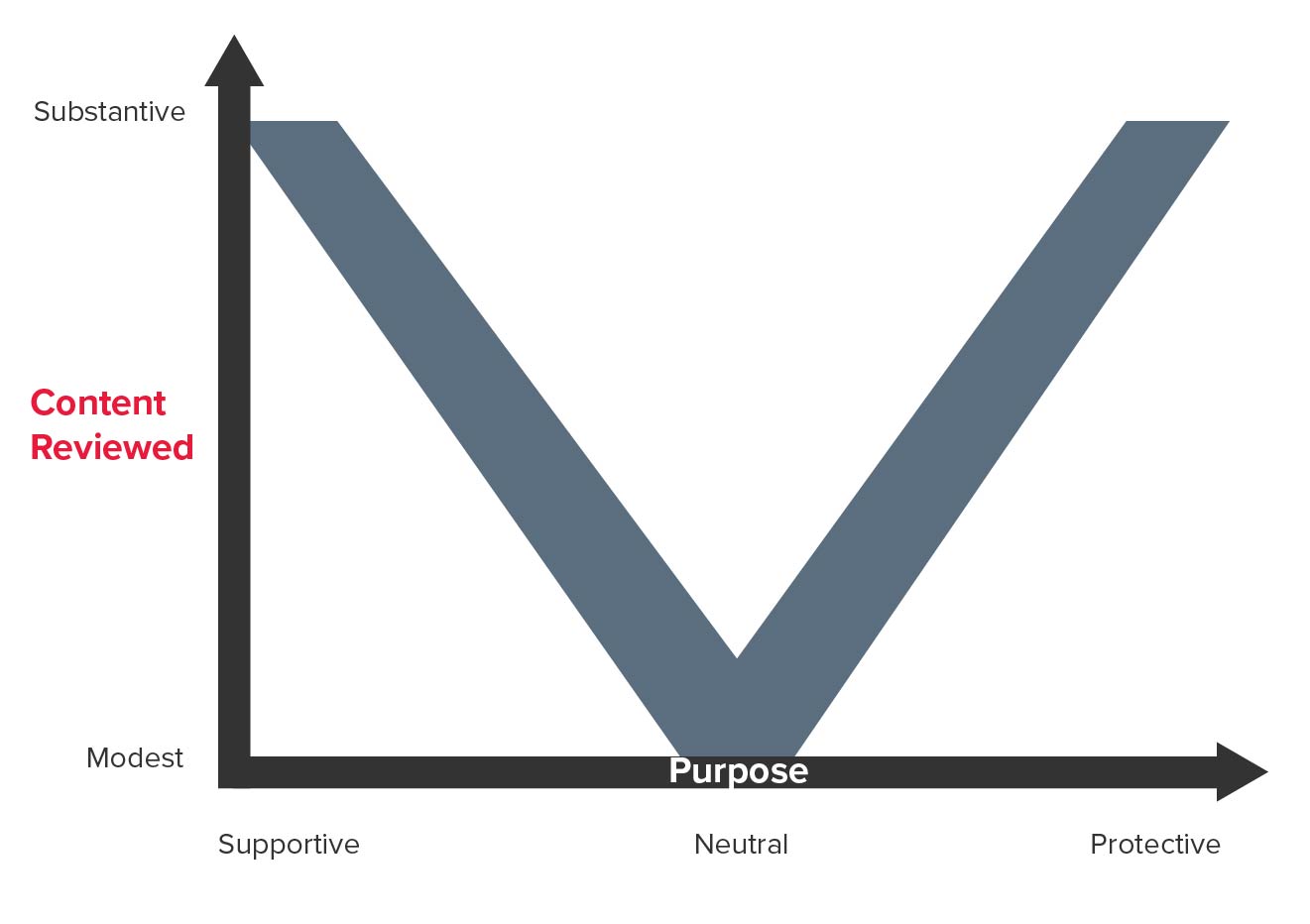

Considering these two dimensions in the analysis, each foundation participating in the study was mapped to the framework based on where on the “purpose” and “content” scales their practices fell. Our key observation was that, for most foundations, there was general alignment between purpose and the extent of the content reviewed, represented in the “v” shape on the graph below. Grantmakers whose purpose in financial due diligence was primarily eligibility verification (“neutral” on the purpose scale) tended to be fairly minimal in the volume and range of grantee information collected and reviewed.

On the other hand, grantmakers that took a more interventionist approach to FDD—whether that was to support grantee capacity or introduce somewhat tighter controls around funds—tended to collect and analyze a more significant amount of data. In most cases, then, the scale of review aligned with the purpose of FDD.

But there are cases where purpose and process may be misaligned. Foundations that indicated that they approached grantmaking in a supportive way but reviewed minimal grantee financial information, may not have adequate information to know what kind of supports to provide. In this case, open and trusting communications that enable grantees to share their capacity needs and priorities may bridge this gap.

Similarly, grantmakers that take a more protective approach but consider minimal grantee financial information in decision-making may risk introducing grant distribution practices or grantee reporting requirements that are not warranted by the grantee’s actual financial situation. These funders may want to consider reviewing more information and/or moving their financial due diligence to a more “neutral” purpose.

Final/Summary Thoughts

Note that our framework doesn’t address explicitly the question of where the burden of financial due diligence data collection falls—on the foundation or on the grantee. Even a substantive review of grantee information does not need to deeply burden grantees with compilation and submission of data and documents. For US-based organizations, much nonprofit financial information is available to the public, including IRS Form 990 filings that report extensively on financial health and activities and, often, annual reports and financial statements posted directly to grantee websites. We encourage funders—even those who take a more active approach in the FDD process—to make as much use of publicly available data as possible to minimize the burden that the process places on grantees.

More broadly, funders may use the findings of this landscape analysis as an opportunity to reflect on their own approach to financial due diligence in their grantmaking practice. They might explore questions such as: What is our purpose for FDD? Is it to identify possible financial challenges among grantees in order to offer them additional supports, or to heighten the guard on our own grant dollars? Does our purpose—whichever it is—reflect our broader grantmaking values ?

We encourage funders to avoid allowing financial due diligence to be an isolated and unexamined part of grantmaking practice. Rather, we invite grantmakers to consider the framework described here and explore adoption of a financial due diligence approach that reflects their broader grantmaking intentions and aligns with PEAK’s fourth principle: Steward Responsively.

1 Note that expenditure responsibility (ER) grants likely require their own approach to due diligence.

SHARE